Understanding Endoscopic Magnetic Esophageal Sphincter Augmentation

Endoscopic magnetic esophageal sphincter augmentation, or magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA), is surgery used to treat GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease). It's done to prevent stomach contents from coming back up into the esophagus and causing heartburn.

Understanding GERD

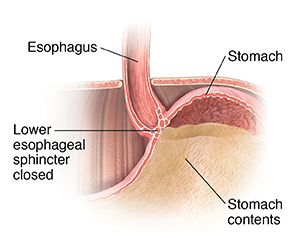

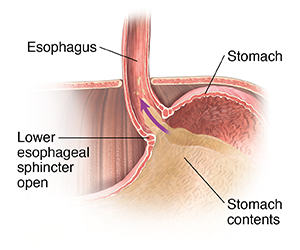

When you eat, food travels from your mouth down a tube called the esophagus to your stomach. Along the way, food passes through the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This ring of muscle acts as a one-way valve. Normally, the LES opens when you swallow. It allows food to enter the stomach. Then it closes completely and quickly. It is natural for the LES to open when you belch, to let air come up. When you have GERD, the LES doesn’t work well enough to hold food and fluids in the stomach. Food and fluid back up into the esophagus. This causes heartburn and other symptoms.

MSA uses a device placed over the lower end of the esophagus, near the LES. The device is made up of magnets. Each magnet is covered in titanium and wired together in a ring. The magnets let the ring get bigger or smaller, almost like a rubber band. When you swallow, the pressure increases at the LES. The LES opens and the ring stretches open to allow food and fluids to get to the stomach. Once the food reaches the stomach, the pressure drops and the LES closes. The MSA ring also closes. This helps keep the LES closed. It helps prevent the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus.

Why MSA is done

Left untreated, GERD can get worse and lead to serious problems over time. GERD can cause pain, bleeding, and trouble swallowing. It can also raise your risk for cancer of the esophagus.

If lifestyle changes and medicines don't help your symptoms, you may need surgery. MSA is one type of surgery that may be used.

Your health care provider will order other tests first to make sure MSA is right for you. MSA wouldn't be a choice for you if:

-

You need an MRI of more than 1.5 Tesla.

-

You have cancer in your upper digestive tract.

-

You're allergic to titanium, nickel, stainless steel, or iron.

How MSA is done

MSA surgery is done using laparoscopy. It uses a thin, lighted tube called a laparoscope (scope). Here’s what happens:

-

You will be asked to sign an informed consent document. Signing this form means you understand both the risks and benefits of the procedure. It also means you've been told about other treatments and that your questions have been answered. Be certain to ask all your questions before signing the form.

-

You’ll have an I.V. (intravenous) line put in to give you fluids and medicines.

-

You’ll be given anesthesia to keep you free from pain during the surgery. You may be drowsy but awake. Or you may be in a deep sleep-like state through the surgery.

-

The surgeon will make several small cuts (incisions) in the belly. The scope will be put through one incision. Surgical tools will be placed through the others.

-

Your belly (abdomen) will be filled with carbon dioxide (CO2) gas. This gives the surgeon more space to see and work.

-

The surgeon will measure the area where the device will be placed. This helps choose the correct size of the device.

-

The surgeon will wrap the device around the bottom of the esophagus and connect the ends.

-

The CO2 gas and all surgical tools will be removed after surgery.

-

The incisions will be closed with stitches or surgical tape.

You will be taken to the recovery room, where you will be closely watched. You may go home the same day. Or you may stay overnight in the hospital. You can go home when your condition is stable, you can keep fluids down, and you can urinate. Because you had anesthesia, you must have an adult family member or friend drive you home. Your health care provider might prescribe medicine to prevent nausea and vomiting.

Risks of MSA

Risks of MSA may include:

-

Trouble swallowing if the LES doesn't relax. This often goes away after a few weeks.

-

Wearing away of the device into the esophagus. If this happens, the device may need to be removed.

-

Bloating.

-

Diarrhea or constipation.

-

Problems related to anesthesia.

-

Allergic reactions. This could happen if you are allergic to titanium, nickel, zinc, or stainless steel.

-

Infection after the surgery.

Follow-up

Keep your follow-up appointments. This helps your health care provider check your progress and make sure that you’re healing properly. Tell your provider if you have any new symptoms or any reflux. And be sure to ask any questions you have.